What is Peloton?

Peloton is a company selling in-home training equipment. See Peloton’s website for more information.

The CEO of Peloton is John Foley. And Peloton was founded in 2012.

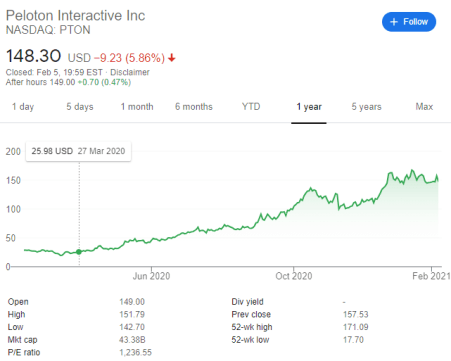

So why are we interested in Peloton? The reason is simple. Its surging stock price.

Peloton announced blowout earnings in the recent quarters, which helped it join an elite club that includes Apple, Netflix, and Tesla. These companies not only delight their customers and create enormous shareholder value; they’re also rewriting some specific, outdated rules on what drives effective business strategy.

To thrive in today’s market, it’s worth understanding exactly what’s behind these companies’ growth, and more importantly how different it is from the way companies used to think.

Let me start with what “good” business strategies look like several years ago.

A quarter-century ago, in their widely acclaimed book Competing for the Future, C.K. Prahalad and Gary Hamel tried to explain why the biggest companies thrive. Their answer: These market leaders identified the part of business they’re best at—be it engineering, product design, manufacturing, supply-chain management, or something else—and they continually reinvest in it. Most everything else is outsourced to third parties.

For example, Walmart exploited its expertise in global sourcing and supply-chain management, but it didn’t bother manufacturing its own products. Toyota, meanwhile, achieved market leadership by excelling in product engineering and manufacturing, but it left its retailing operations to independent car dealers.

This approach gained traction and was echoed by influential business thinkers for decades. It’s why when Apple first announced plans to open company-owned stores and Amazon began designing its own consumer electronics, critical pundits piled on. In 2001, for example, Bloomberg ran a commentary titled “Sorry, Steve [Jobs]: Here’s Why Apple Stores Won’t Work.” And Amazon was often pilloried after launching its first- generation Kindle.

Both the Apple Store and Kindle were huge successes, of course. So what did the critics miss? They were attached to the old “capability-driven strategy”— the idea that companies should focus on what they’re best at. But the idea was flawed and getting old.

For starters, the pundits failed to recognize how a capability- driven strategy can slow companies down. When mature companies cling to outdated skills and assets, they resist disruptive ideas and miss opportunities to serve consumers’ evolving needs. For example, Walmart and Ikea were the market leaders in big-box retailing…but both were dangerously late in e-commerce.

Meanwhile, a new generation of companies were embracing an idea called vertical integration—building and mastering every part of the market themselves. Native e-commerce startups like Warby Parker, for example, recognized early on the potential to expand their market reach through physical retailing. Then they built the requisite omnichannel retailing skills internally.

Vertical integration won’t be right for everyone, but startups should be open to the idea when appropriate. There are three reasons why.

First, at inception, startups often don’t have a deep reservoir of expertise in anything.

There are no assets or manager egos to protect and no sales to cannibalize. This creates a freedom to explore the right strategy for growth.

Second, for highly innovative ventures, they may not find the perfect design, manufacturing, or distribution skills from third-party providers. To live up to its vision, a startup will have to do these things itself. That was the case with both Tesla and Allbirds, which out of necessity were deeply involved in product design, global supply-chain management, manufacturing, and new retailing formats to launch their game-changing products.

Finally, and perhaps most important, vertical integration can give companies more control over delivering superior products and better experiences at every customer touch point. For example, it is now generally recognized that Apple’s tight control over hardware and software design, as well as operating its own company stores, has contributed to superior product performance, customer satisfaction, and price realization.

Peloton, with its rising fortunes, now provides the latest case in point.

In 2011, John Foley conjured up an idea for a “connected fitness” company. The initial plan was to rush a minimum viable product to market by fitting Peloton’s software and electronics to existing bicycle and tablet computers, enabling its products to monitor real-time rider performance and stream online indoor-cycling classes. But at this and several other pivotal milestones along the way, Foley and his cofound-ers decided that the company would be better off developing its own products and internal capabilities, rather than relying on third-party providers.

Then they tackled nearly every part of the business themselves. Peloton designed its own bike, with proprietary hardware and software; recruited and trained its own instructors; developed its own production studios; created its own network of retail outlets; built its own “white glove” delivery and installation service; and more. This was immensely expensive and stressed the company in its early years. But as evidence mounted that it had a superior product and customer experience, the company was able to raise nearly $1 billion in capital.

Peloton went public in September 2019. By mid-2020, it served more than one million subscribers in four countries and generated more than $1.8 billion in annual revenue with strong positive operating cash flow. As a testament to the success of its vertical integration strategy, Peloton currently achieves higher hardware gross profit margins (45 percent), higher customer satisfaction scores (94 NPS), and higher customer retention rates (92 percent) than Apple or Tesla.

This isn’t to say that vertical integration works for everyone. The benefits must be weighed against added investment and operating expenses, management complexity, and the loss of flexibility often found in companies with large legacy asset bases.

So for any founder considering vertical integration, here are three questions to ask yourself before going forward.

- Does owning or controlling assets and capabilities across the value chain significantly improve product performance and customer experiences? For companies like Apple, Netflix, Tesla, Ikea, Allbirds, and Peloton, vertical integration has proven to be a key driver of superior company performance, while also building barriers to competition.

- Can the requirements for capability-building capital be scaled to reflect a company’s stage of development? Peloton tiptoed into retailing, streaming video classes, and white-glove bicycle delivery with small, affordable pilot operations. That’s because it started so early.

- Are your products and services able to generate premium returns? Vertical integration is expensive and can only be justified if your customers are willing to pay for superior performance. That won’t happen in all product categories.

Peloton could say yes to each of these questions. The results speak for themselves—and may serve as a path for many others to follow.

Comments are closed.